Into the Shadow: Jung, Individuation, and the Occult Path of Initiation

“No initiation is real until it descends into shadow. The light that follows is not borrowed—it is earned.”

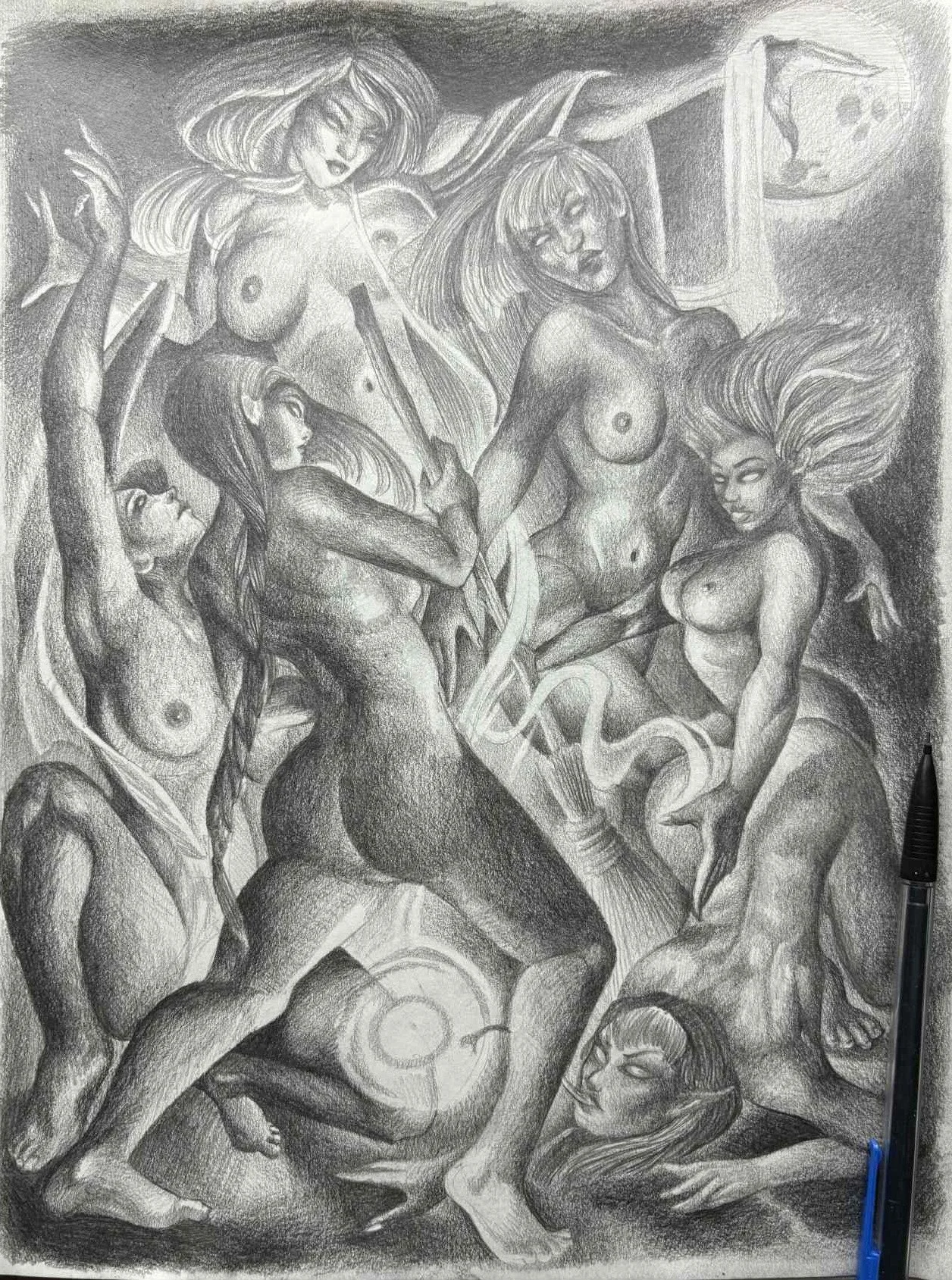

Illustration by Isomara Isodora

Origins of the Term "Shadow Work"

The concept of “shadow work” has become ubiquitous in contemporary spiritual discourse, but its roots lie in early 20th-century depth psychology. The term itself arises from the work of Swiss psychiatrist Carl Gustav Jung, who introduced the concept of the “shadow” as part of his larger model of the psyche. For Jung, the shadow represents the unconscious aspects of the personality that the ego fails to recognize or actively represses—qualities and desires that are incompatible with one’s self-image.

Though Jung himself did not often use the phrase “shadow work” per se, his students and later interpreters began to use it to describe the process of confronting, integrating, and ultimately transforming these repressed elements of the self. It is not a superficial practice—it is a descent into the underworld of the psyche, a confrontation with the disowned parts of ourselves.

Carl Jung and the Shadow

The shadow, in Jungian terms, is both personal and archetypal. It includes not only one’s individual neuroses and denied impulses, but also collective human tendencies such as aggression, envy, and pride. Jung emphasized that ignoring the shadow leads to projection—wherein we see in others what we refuse to see in ourselves. This projection distorts our perceptions and relationships, causing inner conflict and external chaos.

Yet for Jung, the shadow is not merely negative. It also contains creative energy, raw vitality, and aspects of the true self that have been suppressed due to societal norms or psychological trauma. Integration of the shadow is, therefore, not about becoming “darker” but about becoming more whole.

As Jung wrote in Psychology and Alchemy:

“One does not become enlightened by imagining figures of light, but by making the darkness conscious.”

Shadow Work in the Broader Scope of Individuation

Shadow work is a critical stage in what Jung called the individuation process—the path toward psychological wholeness. Individuation is the integration of the various components of the psyche (ego, shadow, anima/animus, and Self) into a balanced and authentic totality.

This process mirrors the alchemical stages Jung studied in medieval and Renaissance texts: nigredo (blackening), albedo (whitening), citrinitas (yellowing), and rubedo (reddening). The nigredo, or dark night of the soul, is where shadow work resides. It is the necessary confrontation with the chaos and pain within, which becomes the fertile soil from which rebirth can occur.

This phase is often painful, disorienting, and accompanied by symbolic death—but it is a prerequisite for the emergence of the deeper Self. Without integration of the shadow, any spiritual ascent is incomplete, even dangerous, as the unacknowledged unconscious will sabotage or distort the emerging personality.

Shadow Work and the Alchemical Nigredo

Jung understood medieval alchemy not merely as an early form of chemistry, but as a symbolic language for inner transformation. In particular, he viewed the alchemical stages of the Great Work—nigredo (blackening), albedo (whitening), citrinitas (yellowing), and rubedo (reddening)—as archetypal phases within the psychological and spiritual process of individuation.

The nigredo—the black stage—is especially relevant to shadow work. It represents the dissolution and decay of the ego’s illusions, a psychic “death” marked by darkness, despair, and confrontation with the unconscious. It is the moment the individual is plunged into their own internal underworld, facing grief, guilt, suppressed rage, and repressed desire. Jung describes it as a necessary descent—a crucible in which the ego is broken open to allow something greater to emerge (Jung, Psychology and Alchemy, CW 12).

For the alchemist, the nigredo was the stage where base matter was reduced to its prima materia. In Jung’s interpretation, this base matter is the unrefined psyche—what must be worked on, purified, and transformed. Shadow work is this labor of the inner alchemist, engaging in psychic fermentation so that something new may be born. The darkness is not an error to be bypassed; it is the condition for transformation. It is a darkness that must be endured, not escaped.

This stage also has planetary echoes—most notably Saturn, who governs restriction, time, decay, and boundaries. Saturn’s heavy hand is felt most acutely in the nigredo, yet it is precisely through that restriction and confrontation with limits that deeper wisdom emerges.

Jung believed that those who skipped or denied this process risked developing a shallow or dissociated spirituality—what he sometimes called “spiritual inflation.” By contrast, those who willingly engaged the black work were being prepared to carry the light more fully in later stages (albedo and rubedo). The shadow, when integrated, becomes a vessel of strength and clarity.

Thus, the nigredo is not simply a psychological crisis—it is a sacred initiation. It marks the soul’s first steps toward alchemical renewal, where even darkness becomes holy.

How Psychology Passed into Ritual Magick and the Occult: Israel Regardie

The bridge between Jungian psychology and modern occultism was built in part by Israel Regardie—an occultist, psychotherapist, and former secretary to Aleister Crowley. Regardie’s most influential contribution was his insistence that magical training must include psychological integration, especially through Jungian principles.

In his magnum opus The Tree of Life and later in The Middle Pillar, Regardie warned that ceremonial magic without psychological grounding could be disastrous. He advocated Jungian shadow work as an essential counterpart to ritual practice. For Regardie, the rituals of the Golden Dawn and related traditions were not just techniques for spirit contact—they were psychodramas that worked upon the magician's inner landscape.

By adapting Jungian principles into magical training, Regardie helped establish a precedent: that personal transformation and magical efficacy are intertwined. Shadow work became not just a psychological process but a magical one—an initiatory passage into deeper levels of spiritual being.

Shadow Work, Spiritual Growth, and Initiation

Shadow work is not optional for serious practitioners—it is foundational. In initiatory systems, whether Thelemic, Golden Dawn, or even certain strains of traditional witchcraft, the aspirant must descend before ascending. The Underworld journey is universal: from Inanna’s descent to Persephone’s abduction, from Christ’s harrowing of Hell to the nigredo of the alchemists.

Initiation, in this context, is not merely ritual enactment—it is an inner event. The magician confronts their limitations, wounds, and illusions not to banish them, but to know them. Shadow work thus becomes the crucible of the soul, where falsehoods are burned away and divine potential forged.

This work can take many forms: journaling, dream analysis, working with archetypes or daimonic forces, or engaging in rituals designed to confront fear, shame, or resentment. The key is honesty. As Jung warned, “People will do anything, no matter how absurd, to avoid facing their own soul.”

Yet the reward is substantial. The integration of the shadow empowers the magician to operate from a place of authenticity, strength, and clarity. It removes the hidden saboteurs of the will. More than that, it opens the door to gnosis—the deep knowing of the Self and its place within the cosmos.

Jungian Alchemy and the Elemental Grades of the Golden Dawn: A Comparative Framework

Both Jungian psychology and the initiatory system of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn share a deep foundation in Western alchemy. While Jung approached alchemy as a symbolic language for the unconscious psyche, the Golden Dawn used alchemical stages as operational templates for ritual initiation and spiritual ascent. A comparison between these two reveals a rich parallel between psychological individuation and magical initiation, especially in the movement through the four elemental grades to the Adeptus Minor degree, corresponding to the sephirah Tiphareth on the Tree of Life.

The Alchemical Nigredo and the Grade of Neophyte (0°=0°)

In Jungian psychology, the nigredo represents the initial descent into psychic darkness—disintegration, confrontation with the shadow, and the death of egoic illusions. This corresponds closely with the Neophyte grade of the Golden Dawn, which is not assigned to any particular element but serves as a threshold. The Neophyte ritual plunges the initiate into symbolic darkness, representing the chaos of Malkuth, where the candidate is blindfolded and led through the Hall of the Neophytes. The goal is to break down the outer persona and begin purifying the uninitiated self.

Jung calls this the regression to the unconscious, necessary to reconstitute the ego in a new relationship with the Self. Likewise, the Golden Dawn recognizes that the first stage of alchemy is putrefaction—a death before rebirth.

Elemental Grades and the Albedo/Calcinatio Stages

The elemental grades—Zelator (1°=10°, Earth), Theoricus (2°=9°, Air), Practicus (3°=8°, Water), and Philosophus (4°=7°, Fire)—each correspond to classical elements and to specific aspects of purification and integration. Jung likened this stage to the albedo, or whitening, where the ego is cleansed through confrontation and symbolic baptism in archetypal energies.

Zelator (Earth) corresponds to calcinatio, the burning away of dross and beginning of discipline. This is where the aspirant learns the foundations of the physical temple and begins to regulate their outer life.

Theoricus (Air) reflects the sublimatio, or ascent into thought and abstraction. Here, the candidate begins to confront mental patterns and the illusions of the intellect—Jung’s "persona" and the inflated ego.

Practicus (Water) mirrors the solutio—the dissolving of rigid identity structures through emotional insight and fluidity. This is a time of dream work, inner visions, and symbolic insight.

Philosophus (Fire) corresponds to coagulatio, the reintegration of self in a purified, passionate form. The candidate must master desire, will, and direction—traits Jung saw as essential in integrating the shadow and reclaiming psychic autonomy.

Jung’s idea of integration at this level parallels the Golden Dawn’s concept of elemental equilibrium. Only after the four elements are brought into harmony can the initiate proceed to the Portal grade, the threshold before Tiphareth.

Tiphareth and the Rubedo: The Grade of Adeptus Minor (5°=6°)

The culmination of the outer order’s work is the Adeptus Minor grade, corresponding to Tiphareth—the sphere of the solar Self, and in Jungian terms, the emergence of the Self archetype. This is where the rubedo, or reddening, occurs: the ego is transfigured through contact with the inner divine. In Jung’s language, this is the point where the conscious personality becomes aligned with the Self—a central archetype representing wholeness, divinity, and purpose.

The Adeptus Minor ritual in the Golden Dawn is deeply solar and messianic in tone. The candidate symbolically dies, enters the tomb of the risen Osiris, and is reborn as an expression of divine harmony. This mirrors Jung’s description of the transcendent function—the symbolic death and resurrection through which opposites are reconciled and higher psychic integration occurs.

In both systems, this is not the end, but a turning point. The true work begins in earnest after this stage. For Jung, individuation continues into ever more subtle layers of the unconscious. For the magician, the Adeptus degree opens the way into the Inner Order, where their theurgic journey continues.

Jungian Alchemy, the Elemental Grades, and Knowledge and Conversation with the Holy Guardian Angel: A Further Comparison

Another notable spiritual event of alchemical significance—worthy of comparison—is the Knowledge and Conversation of the Holy Guardian Angel (K&C HGA), a practice found in The Sacred Magic of Abramelin and later canonized within Thelema and other post–Golden Dawn systems. This transformative process also parallels Jung’s concept of individuation and corresponds most directly with the alchemical stage of rubedo, or reddening.

Jung’s concept of the Self—the archetypal center of the psyche and the axis of true being—bears striking resemblance to how many occult traditions understand the Holy Guardian Angel (HGA). For Jung, the Self is not the ego, but a transcendent, unifying principle that integrates the total psyche. In ceremonial magick, the HGA is often encountered as a distinct intelligence, yet ultimately reveals itself as the higher aspect of the magician—the immanent and transcendent Self.

Aleister Crowley, who inherited and restructured the Golden Dawn system through the lens of Thelema, placed the Knowledge and Conversation of the Holy Guardian Angel (K&C HGA) as the primary goal of the magician’s path. In Liber Samekh and The Vision and the Voice, he describes it as the union with one’s True Will, achieved through inner purification and focused invocation. He aligns this experience with the sephirah Tiphareth—the same sephirah where the work of Adeptus Minor occurs.

The Knowledge and Conversation of the Holy Guardian Angel and the Adeptus Minor both represent transformative encounters with the divine Self, but they are not entirely synonymous.

By contrast to the structured ritual of Adeptus Minor, the K&C HGA is not only a recognition of the divine center—but a living, dynamic relationship with it. In many accounts, this is not merely symbolic but an actual spiritual experience: the emergence of a distinct, intelligent presence that instructs, purifies, and guides. Crowley saw this not as a step on the path, but the path itself. It is not simply a rite—it is a life-altering conversation that reorganizes the soul's entire orientation.

From a Jungian perspective, this distinction reflects different moments within the alchemical process. As noted above, the Adeptus Minor ritual corresponds closely with the rubedo—the moment the fragmented psyche is reconstituted around a stable center. It is the crystallization of inner work that followed the nigredo and albedo, a solar moment of unified vision and psychic reintegration. The K&C HGA, however, could be seen as a step beyond symbolic integration—where the Self is not merely understood, but encountered as numinous Other. In Jung’s own words, this is the “transcendent function” in action: the emergence of new psychic wholeness that bridges conscious and unconscious, ego and archetype, human and divine.

In this sense, the Adeptus Minor and the K&C HGA reflect two levels of transformation. The former marks the psychological realization of the Self archetype; the latter inaugurates the living relationship with it. One is integrative, the other relational and revelatory. Both are alchemical milestones in the broader journey of individuation.

Thus, while both paths share the same terrain—Tiphareth, the Sun, the Self—their methods and emphasis differ. The Adeptus Minor experience is structured, initiatory, and aligned with collective ritual. The K&C HGA is often spontaneous, deeply individual, and intensely relational. In the language of alchemy: rubedo crystallizes the Self; K&C HGA makes it speak.

Both are necessary. One prepares the temple; the other speaks from within it.

While Jung did not believe in the literal invocation of spirits, he did believe that archetypes could function autonomously and carry numinous power offering us a convergence of the psychological and magickal. The Angel, in this view, would be a manifestation of the Self in symbolic or visionary form. Magicians, however, treat the Angel as both psychological and metaphysical: a real presence that calls them into alignment with their higher destiny.

Thus, we see convergence. The psychological individuation process and the ceremonial path to K&C HGA are two maps of the same territory. Both require purification, descent into darkness, confrontation with the shadow, and a final transfiguration through divine encounter. Both recognize that true spiritual maturity is not found in escapism or fantasy—but in the conscious integration of all aspects of the self, culminating in service to a deeper, divine purpose.

Final Thoughts: The Way Down Is the Way Up

Shadow work, when taken seriously, is not a side practice or psychological footnote. It is a mystery rite in itself. It is a necessary phase of spiritual alchemy, a confrontation with the demons of the inner world so that we may stand in truth before the spirits of the outer one.

If we avoid the shadow, we practice illusion—not magick.

But if we embrace it—if we dare to know ourselves in full—we walk the ancient path of the initiate, guided not just by light, but by the wisdom found in darkness.

—

Frater Henosis

Bibliography

Abramelin the Mage. The Book of the Sacred Magic of Abramelin the Mage. Translated by S. L. MacGregor Mathers. York Beach, ME: Weiser Books, 1997.

Cicero, Chic, and Sandra Tabatha Cicero. Self‑Initiation into the Golden Dawn Tradition: A Complete Curriculum of Study for Both the Solitary Magician and the Working Magical Group. St. Paul, MN: Llewellyn Publications, 1995.

Crowley, Aleister. Liber Samekh (Theurgia Goetia Summa). In Gems from the Equinox, edited by Israel Regardie, 503–22. York Beach, ME: Weiser Books, 1988.

Crowley, Aleister. The Vision and the Voice: With Commentary and Other Papers. York Beach, ME: Weiser Books, 1998.

Edinger, Edward F. Anatomy of the Psyche: Alchemical Symbolism in Psychotherapy. Chicago: Open Court, 1985.

Greer, John Michael. Inside a Magical Lodge: Group Ritual in the Western Tradition. St. Paul, MN: Llewellyn Publications, 1998.

Iamblichus. On the Mysteries. Translated by Emma C. Clarke, John M. Dillon, and Jackson P. Hershbell. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2003.

Jung, Carl Gustav. Aion: Researches into the Phenomenology of the Self. Translated by R. F. C. Hull. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1979.

———. Modern Man in Search of a Soul. Translated by W. S. Dell and Cary F. Baynes. New York: Harcourt Brace, 1933.

———. Mysterium Coniunctionis: An Inquiry into the Separation and Synthesis of Psychic Opposites in Alchemy. Translated by R. F. C. Hull. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1977.

———. Psychology and Alchemy. Translated by R. F. C. Hull. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1980.

———. The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious. Translated by R. F. C. Hull. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1981.

Jung, Carl Gustav, and Marie‑Louise von Franz. Man and His Symbols. New York: Dell, 1964.

Kraig, Donald Michael. Modern Magick: Twelve Lessons in the High Magickal Arts. 2nd ed. St. Paul, MN: Llewellyn Publications, 2002.

Regardie, Israel. The Middle Pillar: The Balance Between Mind and Magic. Revised ed. Edited by Chic Cicero and Sandra Tabatha Cicero. St. Paul, MN: Llewellyn Publications, 2005.

———. The Tree of Life: A Study in Magic. 3rd ed. St. Paul, MN: Llewellyn Publications, 2000.

Von Franz, Marie‑Louise. Alchemy: An Introduction to the Symbolism and the Psychology. Toronto: Inner City Books, 1980.

Zalewski, Pat. Inner Order Teachings of the Golden Dawn. St. Paul, MN: Llewellyn Publications, 2006.